As we crash land into 2017 – and the start of my “serious” research year – I am starting to feel the weight of this doctorate settling on me. Perhaps like the famous elephant being felt by several blind men in search of THE TRUTH. I remember this feeling from my time as CAMRT president, looking back I have a sense of wonder that I actually worked full time, carried on raising two children and simultaneously managed a huge work load as board chair (including hiring a new CE in complete ignorance of executive searching and an inordinate amount of travel). I am in awe of my past self, and wondering if that was a fluke or I can manage something similar with this next stage of research – despite having less brain cells, fluctuating hormone levels that make me doubt my sanity and no letup in the demands of an equally hormone-raddled 15 year old and a 10 year old entering the years of sarcasm and parental-loathing.

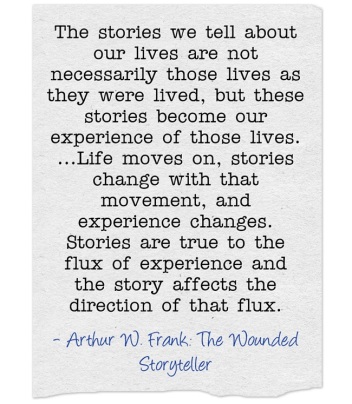

But when all else fails, there are always books, and stories, and language to give us solace. Reading any blog, or listening to people talk about their doctorates you can’t help but trip over the word “journey”. We communicate with metaphor – after finishing my narrative inquiry course I am constantly struck how much we explain something by using another thing! Even my EdD notebook has the words “Go your own way” on the front*. Illness narratives – or any kind of quest – are often framed as journeys. Arthur Frank described the “shipwreck” metaphor that people with serious illness often use. Picking up the pieces, losing their compass, feeling adrift, rebuilding the boat, getting back afloat…. The doctoral journey metaphor is a well-worn path (see what I did there?) – we encounter bumps in the road, sudden and unexpected turns, the journey may be arduous and long but we can often see the end of the road and feel triumphant when we reach it.

For your education and amusement, then, I have collated an initial list of other metaphors used by my EdD cohort and professors this weekend. Enjoy them and feel free to post others you have used/know in the comments!

The builder: the research process relies on a strong foundation; a good blueprint is essential, take time to lay the foundations well before you move ahead because you want your final edifice to be sturdy and strong.

The oil slick: your project may look amorphous and unformed, you may need to contain the boundaries, don’t let it spill over or you will lose control.

The dance: you need to start slowly and learn the basic steps, once you get into the rhythm you will gain confidence, eventually you will throw yourself into a whirlwind of artistic self-expression that is uniquely yours.

The sculptor: out of the raw clay of passion and intent will emerge the idiosyncratic and beautiful piece of work that is your contribution to the academic world. Take care to hone your tools, and think twice before you chip off a chunk, you may need to measure twice and cut once (OK, that one is a tailoring metaphor….)

The party: picking up the basics of your theoretical framework and positionality is like coming late to a party (except probably there is no wine, and you don’t have to dress up). There is a conversation going on around you (probably about Foucault) and you have to place yourself within it, figuring out what you need to say to add to the ongoing discussion.

The lightbulb: this is a bit of a cheat but one member of my cohort suggested her dissertation should be called “fumbling around in the fucking dark”. I liked it so much I decided it needed to be kept for posterity.

*The only excuse I have for this is that it was 50% off.